“Deaf people make excellent architects and being deaf means that we are naturally visual people;

we can see what needs to be done in a space.” Chris Laing, architectural designer and activist.

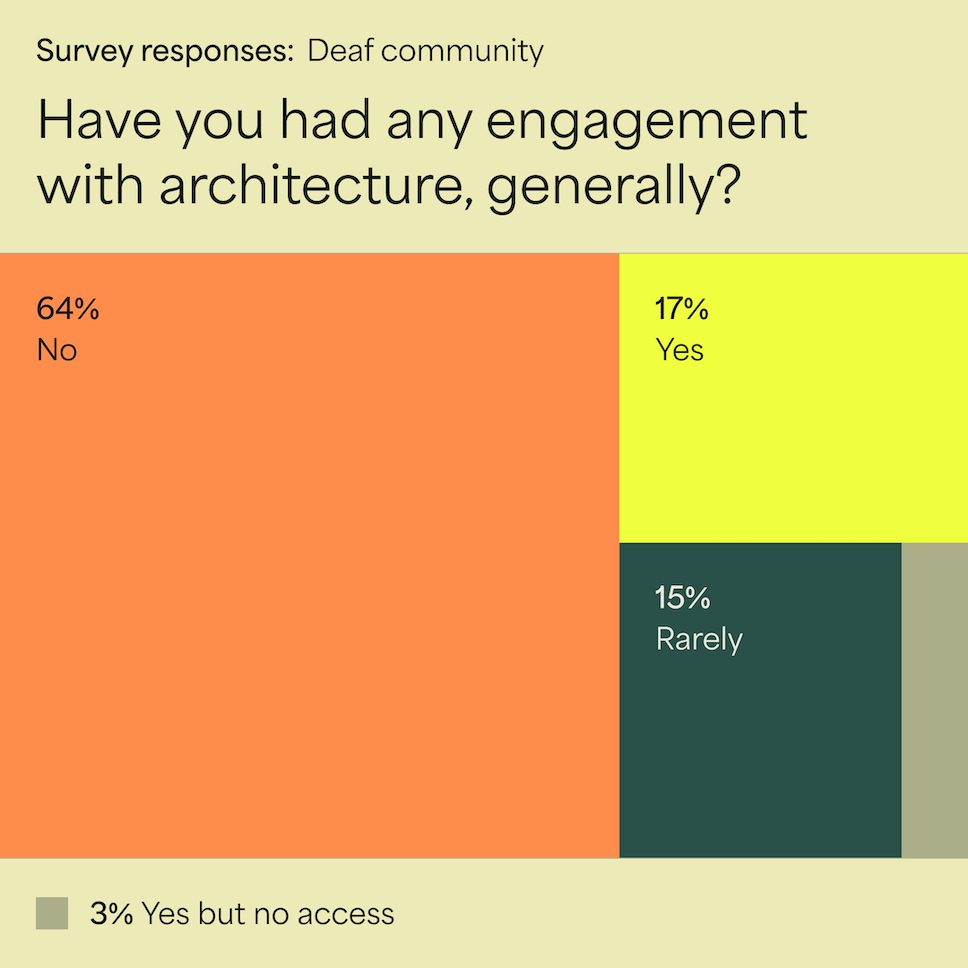

An advocate for inclusivity in architecture, Chris Laing has launched Deaf Architecture Front (DAF), a platform and campaign that aims to break down barriers for deaf people working within the field of architecture.

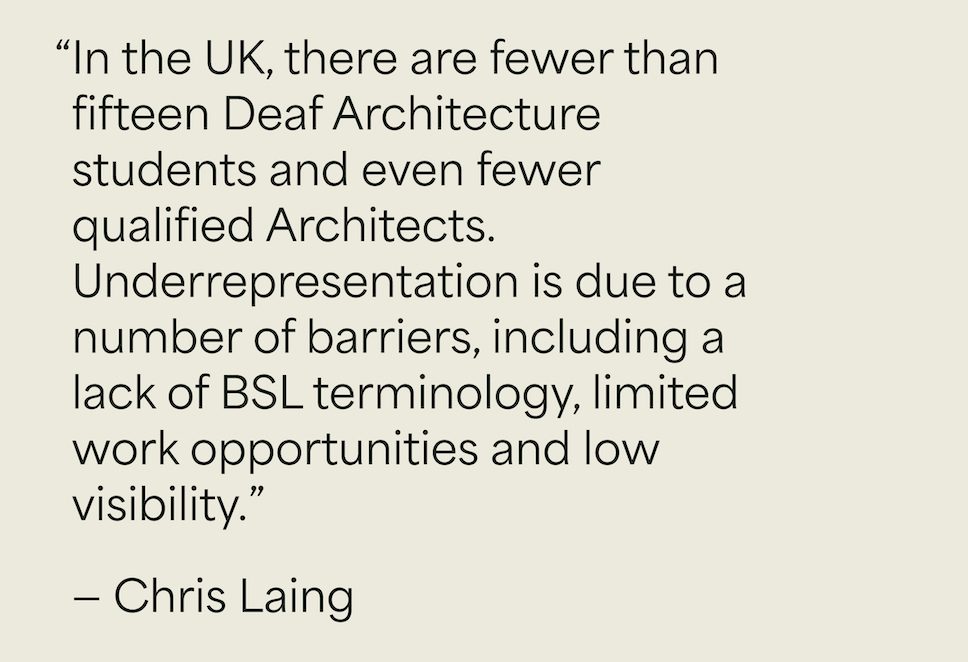

As a hugely important voice, particularly at this time when there are very few qualified deaf architects in the UK, Chris Laing has first-hand experience of spatial injustice and the lack of opportunities in the built environment. He is striving towards positive change, focusing on building a better future for the deaf community.

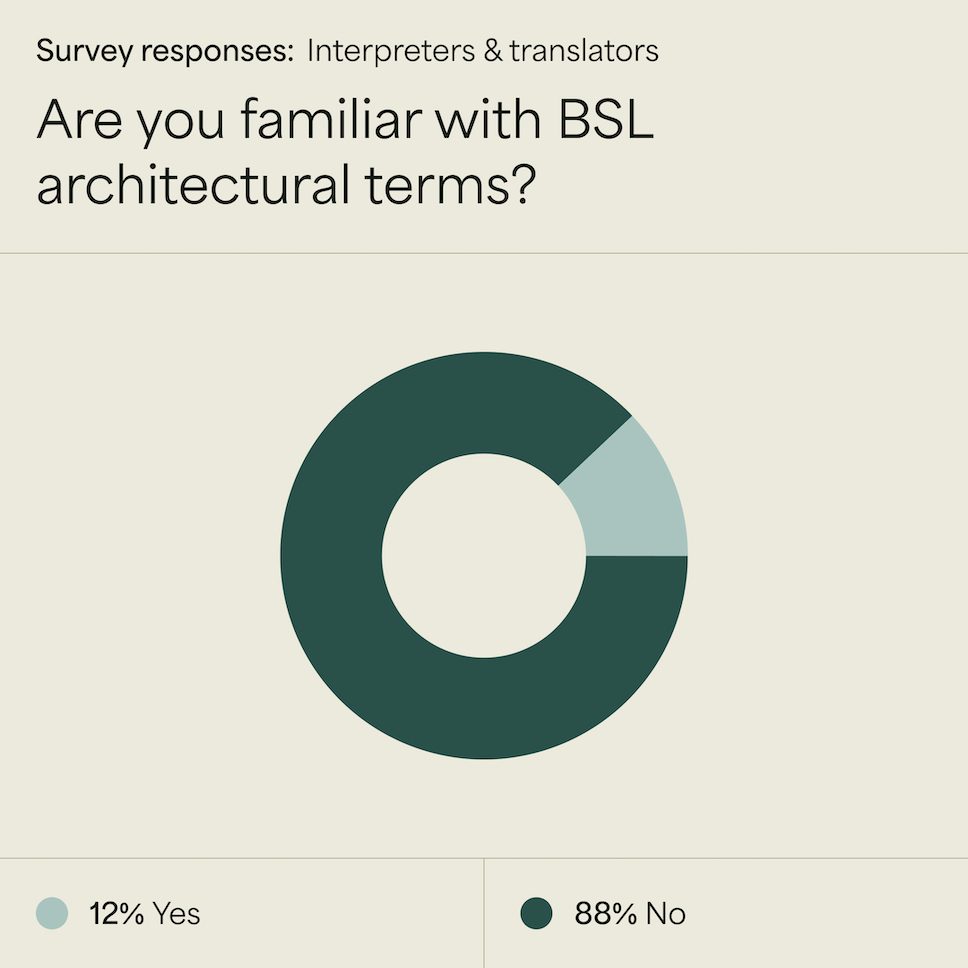

His mission is to create better accessibility through Signstrokes, which is an online resource addressing British Sign Language’s lack of signage for specialist architecture terminology (co-founded with Adolfs Kristapsons). Alongside this, DAF is campaigning to adjust the accessibility guidelines, which currently don’t provide enough information about DeafSpace, and striving to give deaf students better work placement opportunities and more routes into the industry.

We took the opportunity to talk to Chris Laing about the recent launch of DAF and what the initiative sets out to achieve, as he reveals what drives his ambition to take action and explains what questions still need to be asked to ensure inclusivity in the worlds of architecture and design keep improving…

Can you tell us a bit about yourself, your background, and how you’ve got to where you are today?

My family is hearing and I was born profoundly deaf. As a deaf child, I was always very visual and knew by the time I was 8 years old that architecture was for me.

As a black deaf architect in the deaf community for architecture, I found that there was a distinct lack of opportunities and role models, which had a huge impact and indisputably delayed my journey to becoming an architect. Had I not had to fight through these barriers for accessibility, resources, role models, and more, I would have become a qualified architect five years ago. So now, my aim is to give future generations better opportunities than I had.

My personal journey to working within architecture was an arduous one. I faced numerous barriers and remained stoic, repeatedly telling myself not to give up. On my journey I met other deaf students whose dreams were crushed by the lack of access provision; I kept thinking this is not justifiable, something needs to change. Society needs to change, because society is the barrier, and I am here to make that change.

What initially inspired you and continues to drive your ambition to take action for spatial justice and inclusive design in the built environment?

As I grew up, I started to notice things in my environment that represented spacial injustice. For example, I recognised that tables were oblong or square in shape and this suits hearing people but deaf people would prefer round tables, as they provide eye lines and support communication.

When I did my MA, I looked at access documents and wondered where is the guidance on spaces for people to sign in? I discovered that some of those changes have started in America and I think we need that here in the UK too.

I went travelling to Rome in Italy and visited a deaf-owned restaurant called One Sense by Valla; it had a huge impact on me as the space was not only inclusive for deaf people but for everyone. There was a lot of transparency in the space, for example customers can see through into the kitchen and there are mirrors behind the bar. The use of mirrors not only allows deaf people to see what is going on behind them while waiting at the bar, but it also ensures a deaf barista can see reflections in the mirror whilst making drinks. When I came home, I decided I need to make sure I capture all these design elements in my thinking.

Deaf people make excellent architects and being deaf means that we are naturally visual people; we can see what needs to be done in a space. We have all the requisite skills but few of us make it to be qualified architects. I think I could support the integration of deaf people and make everyone feel included along the way.

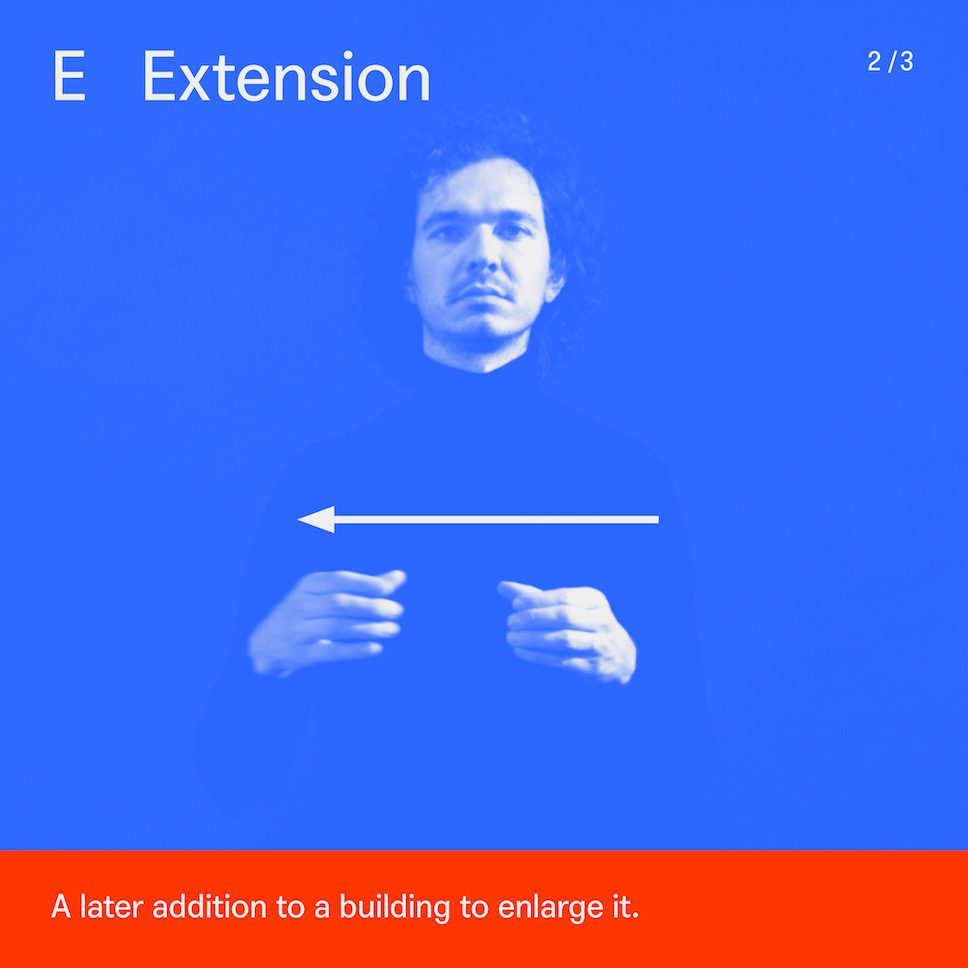

What has been involved in founding Signstrokes and how important do you think this is in helping to increase the number of qualified deaf architects in the UK?

Signstrokes is a process of trying to create signs that match architectural terms, and to achieve this it is vital to talk to people in the deaf community. We need to make sure that terminology is not just spelled out to people, but actually put into a visual sign so that it is easily recognisable for deaf people.

This will create better accessibility for the deaf community who want to become architects because they will have BSL (British Sign Language) translation with BSL architectural terms. The aim is to break down barriers and to support the deaf community with a clear guide to help them become qualified architects.

What would our cities look like if they were designed for the deaf?

A city would have open spaces, so you would be able to see what is coming and what is around the corner. There would be BSL signage and, above all, a deaf-designed city would be a safe place for people to co-exist.

You have just launched Deaf Architecture Front (DAF). Can you tell us more about this initiative and what it sets out to achieve?

DAF aims to remove barriers for deaf people working within the field of architecture, so that entry into the profession is a more level playing field. It will seek to fill the gaps, enabling deaf people to have positive role models and see that they have place in architecture in a professional sense.

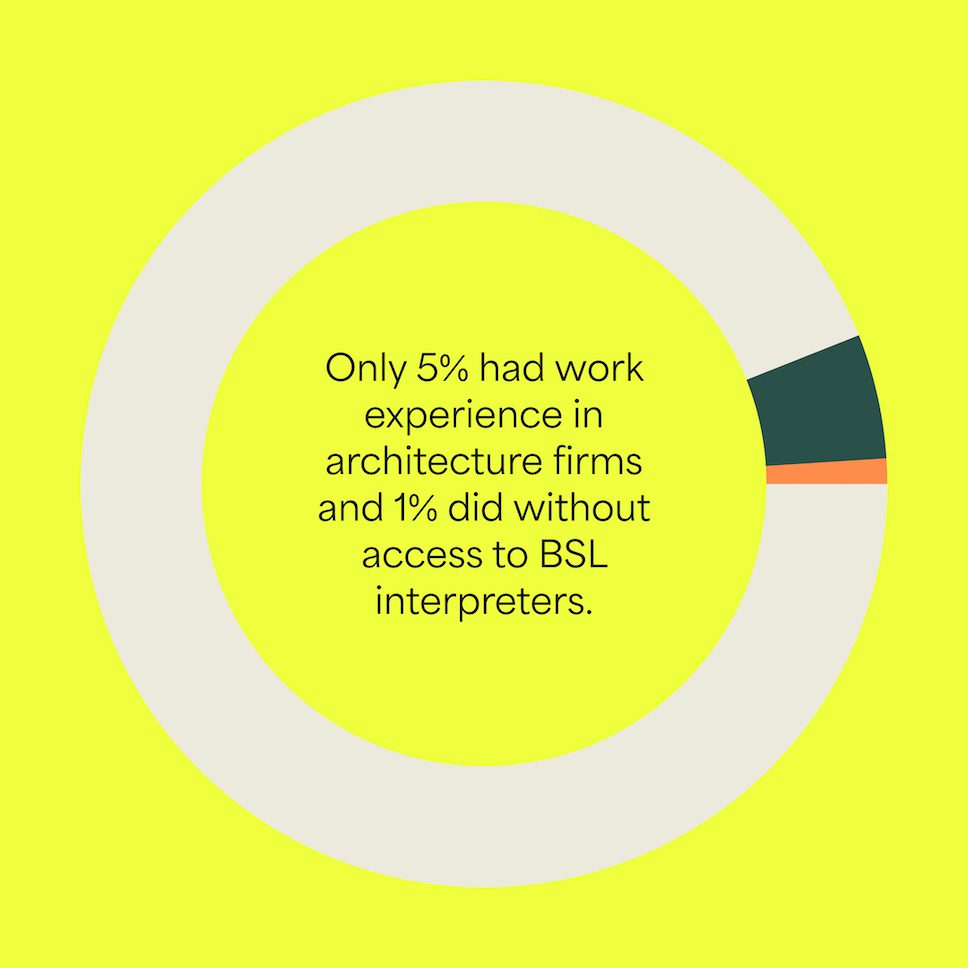

To improve opportunities, DAF would be looking to fund BSL interpreting to put deaf students into work placements within architecture, allowing students to leave with a good understanding of the process involved in working with a client to achieve a brief.

The platform will seek to create possibilities for deaf community engagement within architecture, such as tours, public consultations, events, or workshops. We will also create safe spaces for deaf architects and designers to share tips and experience, to eliminate the feeling of isolation that comes from many hearing office spaces.

A high percentage of the deaf community uses BSL as a first language, so many resources are not accessible for deaf people. Therefore, DAF will create BSL formats to access for the deaf community, including work with BSL translators (these are deaf people who work within RIBA and the higher education sector to allow the smooth transition of deaf people through the education system.) DAF will campaign to adjust the accessibility guidelines as they currently don’t provide enough information about DeafSpace (an approach to architecture that is primarily informed by the unique ways in which deaf people live and inhabit space).

What are the important questions that need to keep being asked to ensure inclusivity in architecture and design keeps evolving and improving?

These are a few questions that spring to mind:

- Have deaf people been given accessible materials that make sense to them?

- Have we followed the guidelines within the context of the consultation within each minority community?

- Have you given several options for format for the deaf community’s feedback (as they may wish to raise their concerns in BSL)?

- Have you raised your concerns or the concerns of other people regarding deaf access?

- Have you made sure the local authority is promoting your consultation through their contact with local deaf people?

- Do you reach out to deaf schools to offer them work experience at your workplace?

Photography by Ashton Jean-Pierre; Signstrokes and DAF infographics and visuals are courtesy of Chris Laing.

Learn more about Chris Laing’s inspiring initiative Deaf Architecture Front (DAF) on Instagram.

Read more architecture news on enki and don’t miss our interview with London Festival of Architecture Director Rosa Rogina as she reveals more about what this year’s Festival will bring, including ways to make our built environment more accessible and inclusive to all.